Age Shall Weary Us

The Author under 30. Considering his best creative work.

Last year I met the parents of the friend of one my step-children. He was a retired Naval Officer, she a semi-retired nurse. As we stood in the kitchen exchanging small talk over a cup of coffee I was struck how like the archetype of parents they were. Then another thought struck me; wasn’t I an archetypal parent as well? After all, give or take a year we were the same age, I had children too, we discussed the iniquity of university tuition fees, we shared concerns about our children’s future in the ‘current climate’, we worried how they would ever afford to buy a house and laughed about them looking after us in our old age. Damn! Despite of how I perceived myself I was looking into a mirror – I am not 17, I’m 57.

At 57 I’m not old. Over half way through my life for sure but inch’allah a good few more years to come. Nevertheless, it’s sometimes hard to block dark thoughts about creeping time, foremost amongst of which is the widely-held conviction that your best work is done before you’re 30. If this is true, then I’m nearly three decades past my best and if that’s been my best it was a pretty shoddy effort.

What do we mean by work?

So is it true and exactly what we mean by ‘work’? The scientific definition (the use of force involved in moving an object a distance when that the force and the motion of the object are in the same direction) implies a kind of kinesis and in a way that’s about as fine a stripped-down version of a life as you could get. Whilst we live and breathe, however idle we may be, there’s no denying the biological forward motion inherent in our beating hearts pumping blood to cells and vital organs. But whilst we are to be congratulated to some extent for nurturing our autonomic reflexes by not smoking, ingestion too much saturated fat and trying to stay off the bottle at least one day a week, for most of us simply staying alive doesn’t call for a medal ceremony.

Perhaps then a more useful definition might be the one that involves both physical and mental effort – the one over which do have control. But if we’re considering achievements in the context of age then surely we must discount the purely physical. It’s axiomatic that our best physical work is done before we’re thirty, that’s just biology. It stands to reason that we’re never going to run 100 metres faster at 80 than we did at 30 – unless we’ve moved to Mars and learned how to breathe carbon dioxide.

It’s the work of our minds that are important here and unfortunately the evidence for early age bias is somewhat compelling. Clear using 30 as an absolute milestone is a little churlish. As great things have been done by 31 and 32 year olds we must accept 30 as the mean. No one disputes that but move the marker out to 40 and it’s quite remarkable how many great things have been achieved by minds not yet four decades old. But what is ‘great’ and does a definition of greatness matter? The novelist Mary Wesley is frequently trotted out by the oldies as a shining example of the late starter. Her first novel Jumping the Queue was published in 1983 when she was seventy and between then and 1997 she published ten more. However, whilst there’s no doubt that she was an accomplished and entertaining writer even her closest friends would be unlikely to call her a great one.

What is ‘Greatness’?

But before embarking on a discussion of greatness, a little qualification is required. As alluded to above, when considering greatness before the age of 30 we must discount the physical. Great though Babe Ruth, Pele, Mohamed Ali, Don Bradman and Lionel Messi may have been, nothing they did can be said to have moved the world along that much. Equally great explorers from Ernest Shackleton to Neil Armstrong, whilst they may have been involved in activities that lead to greater understanding, it’s hard to argue that they themselves were directly responsible for any notable ideas. At the heart of this argument is creativity. The big question is, do humans possess the ability to be truly creativity only up to the age of 40?

A definition of Creativity

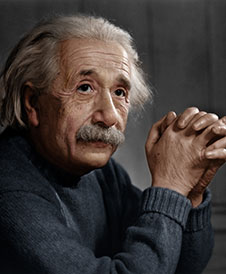

What exactly do we mean by creativity in this context? When deconstructing the processes behind examples of great human discovery and invention a clear pattern emerges. All start with an impasse; light travels in waves doesn’t it? So why are there two dots on the card when I fire a beam of light through a single hole? Why do birds have feathers and humans talk? Why should painters only observe objects in a single plain? Then Einstein discovers wave particle duality, Darwin develops the theory of evolution and Picasso develops cubism. Creativity then is a journey which starts at one point and moves to another, at a moment when that point was not yet discernible. As Einstein himself said ‘Logic can take you from A to B but imagination can take you everywhere’.

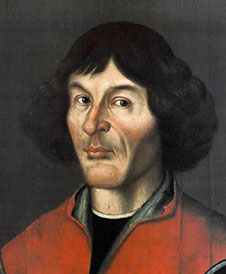

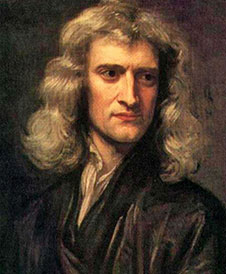

It is perhaps worth mentioning, especially for any pedants who might be reading this, that the creative journey apparently undertaken by one individual is seldom straight-forward. This is what Newton was alluding to when he talked of the shoulders of giants. Generally we are happy to accept that Copernicus ‘discovered’ that the earth orbited the sun, that Newton ‘discovered’ calculus and that Watson and Crick ‘discovered’ the structure of DNA. But all of them needed giants’ shoulders to see the new horizon. Was Copernicus’s heliocentric theory not influenced by observations as far back as the third century CE? Did Newton or Leibniz invent calculus? Would Watson and Crick have been able to make their discovery without Rosalind Franklin’s remarkable X-ray images of DNA three years before? Whatever the truth, it is reasonable to suggest that there are those throughout human history who have taken the evidence that existed (whether seen from an elevated position from the shoulders of their peers) and used their creativity to reveal something entirely new.

All the examples mentioned in the previous paragraph refer to scientific achievements and in building arguments for against the ‘before 40’ theory, scientific achievement is easy to define and easy to pinpoint. We know the exact days on which Rutherford split the atom1, Fleming discovered penicillin and the human genome was finally sequenced. Even further back in time it’s a matter of record when Priestly discovered Oxygen (August 1, 1774), when Franklin risked death by wafting steel rods about in a thunder storm (May 1752) and when Galileo first published his planetary observations (March 13, 1610) – not sure when the apple fell on Newton’s head – probably not true. With such calendrical accuracy, plotting a graph of age and achievement in science is straight-forward and the evidence is compelling.

Who Are the Greats?

But who are the greats? Creating this kind of list has been the stuff of dinner parties since tables and chairs were invented. However, to narrow the field let’s take ‘world changing’ as a measure. From this some indisputable candidates emerge. Here’s a list of some of the premier league:

COPERNICUS

Heliocentricity. Age: 31

NEWTON

Principia Mathematica (see below)

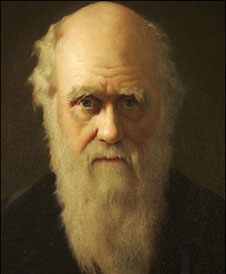

DARWIN

The Origin of Species (see below)

I’m going to bend the rules with these two a bit. Newton was 44 when Principia Mathematica was published and with The Origin of Species Darwin was 50. However, they both undoubtedly had all their ducks (or in Darwin’s case, finches) in a row a good ten years before – for Darwin only fear of the consequences and the fact that Alfred Wallace was getting awfully close to the same conclusion flushed him out. So, Darwin Age: 39 is perfectly fair and it wouldn’t be stretching it to say 29 and Newton, let’s generously say 35 by the time he’d got thermodynamics nailed down.

EINSTEIN

Special Theory of Relativity: 26

General Theory: 36

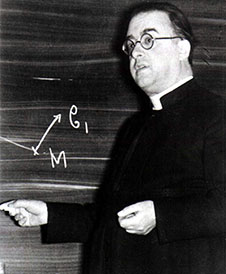

GEORGES LEMAÎTRE

Big Bang Theory. Age: 33

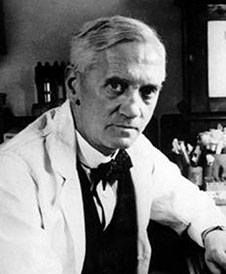

FLEMMING

Penicillin. Age: 47 (ok, an exception)

WATSON & CRICK

Structure of DNA. Ages: 25 & 37

BERNERS-LEE

TCP/IP, The Internet. Age: 34

I could go on but trust me, 40’s a real upper limit for scientific breakthrough and you don’t lose too many by lowering it to 30.

The Scientist v The Artists

So much for scientific creativity; what about the arts? The definition here seems much less clear-cut. Can it really be argued that a novel or a painting or a musical composition can have begun at point A and moved to point B where point B was not discernible at the time? At first perhaps not, especially if we use the rather narrow measure that great creativity changes the world. It’s a moot point as to whether War and Peace, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony or Picasso’s Geurnica did so, but if we drill down a little it’s definitely true to say that these things changed their world. When Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe outraged Parisian society in the 1863 Salon des Refusée Impressionism was on the map and the world of painting was changed forever. In this sense there is no difference between the two disciplines; whether scientific or artistic, a definition of great work still includes a great creative mind. So what does the list look like for the creative arts?

Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe – Impressionisms first great bomb-shell

Whilst it may not be as clear-cut as for the scientists, Raphael, Shakespeare, Caravaggio, Jane Austen, Tolstoy, Shelley, Mozart, Beethoven, Dickens, Manet, Picasso, James Joyce, Stravinsky, Orwell, Virginia Woolfe and Sylvia Plath are just a few of the notable painters, writers and musicians who greatest works were behind them by the time they reached forty.

Ah! But I hear you say – surely you have simply chosen people whose profile fits with your argument? What about ‘X’, he was 856 years old when he discovered ‘Y’. The point is, there are some notable exceptions in all fields but these are mostly in areas that require perseverance, bloody mindedness and physical ability. Searching for ‘achievers over 60’ (and related terms) on the internet returns people who have either achieved great personal goals such as parachuting out of an aircraft at 100 or climbing Mount Everest at 80 or people who have done notable things in later life but generally after a lifetime of doing similar things. There very few who have done their best creative work over 40. That said, there are a couple of other issues that we ought to consider before drawing any conclusions. Firstly, is there a gender aspect to this? Secondly is life-expectancy an issue?

Is Gender and Issue?

At first glance there might appear to be a gender skew – there are very few women who have done ‘great’ things under the age of 40. However, it doesn’t take a genius to work out that has nothing to do with women per se, but everything to do with women’s historical status in the world. It’s a matter of quantity not quality. To take just one example the remarkable Augusta Ada King-Noel2, Countess of Lovelace,

whose contribution to the world of mathematics and computing remains unknown to most but revered amongst the cognoscenti, was just 25 in 1840 when she was making outstanding contributions to the nascent world of computing. Marie Curie was 31 when she discovered radium and polonium, Jane Austen 38 when she wrote Pride and Prejudice, Virginia Woolfe, 33 when she wrote Mrs Dalloway and Sylvia Plath who had written all she had to write before committing suicide at the age of 31. A glance down the canon of outstanding female creative works, and one sees no difference in the pattern for that of men.

whose contribution to the world of mathematics and computing remains unknown to most but revered amongst the cognoscenti, was just 25 in 1840 when she was making outstanding contributions to the nascent world of computing. Marie Curie was 31 when she discovered radium and polonium, Jane Austen 38 when she wrote Pride and Prejudice, Virginia Woolfe, 33 when she wrote Mrs Dalloway and Sylvia Plath who had written all she had to write before committing suicide at the age of 31. A glance down the canon of outstanding female creative works, and one sees no difference in the pattern for that of men.

Marie Curie was 31 when she discovered radium and polonium

What about Life Expectancy?

On the question of life-expectancy, it’s worth considering whether knowing you are unlikely to live beyond 35 in eighteenth century England, for instance, might add a certain urgency to your endeavours. Indeed, until the problem of how to mass produce penicillin was solved in the later 1940s and with it the concomitant rise in life-expectancy worldwide, it might be tempting to suggest that anyone with ambitions to achieve greatness better jolly well get on with it. Tempting, but nonsense – for two reasons. Firstly, even in times of high mortality rates human nature forces to believe that the bullet is coming for some other poor sod. It’s simply not conceivable to imagine that Newton, Copernicus, Galileo and the like got the skids under their work under the shadow of certain death before their fortieth birthday. Certainly many did succumb; undoubtedly disease, famine, war and all manner of other causes have carried off the potentially great but it’s tough to argue that fear of such things accounts for prodigy.

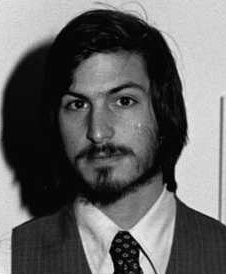

In fact statistics just don’t stack up. If it were true that fear of imminent death drives great work then great workers should be getting older. This just isn’t the case. The sub-forty trend continues throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty first. In fact, judging by the profiles of the Silicon Valley genii, the upper age limit is, if anything, coming down. Bill Gates of Microsoft, Steve Jobs of Apple and Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook were 20,21 and 20 respectively when they launched their tech enterprises. Serge Brin and Larry Page just 25 when they started Google, whilst Travis Kalanick is positively conventional for being 33 before founding Uber. Demographic profiling isn’t going to help.

Steve Jobs: 20 years old when he founded Apple

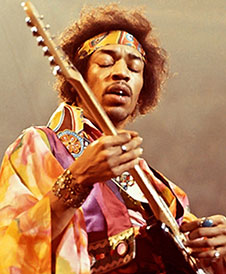

Finally perhaps we should examine the question of whether actually dying young has an bearing. The significant number of creative greats whose lives have been cut short, either through accident, illness or at their own hands gives a possible impetus to idea that, had they lived they might have gone on to greater things post-forty. Poets in particular seem to have a tendency to exit early. Just what would Shelley, Keats, the Great War poets, Sylvia Plath and Dylan Thomas have done had they lived their allotted four score years? Then, would Mozart have written another 600 works of genius if he hadn’t ended up in a pauper’s pit at the age of 35? What great thoughts would Frederic Nietzsche had if he not gone stark, staring mad in his forties? Where would the world of popular music have gone if Hendrix, Holly and Jim Morrison been taken from us prematurely? Who can say? However, from an actuarial point of view not enough creatives have died young to having any bearing on the figures and, based on empirical evidence whatever they might have produced would not have had the shining originality of their earliest works.

If he had lived would Jimi Hendrix have done his best creative work at 80?

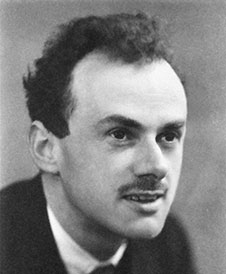

As we have already seen, moving from science to the arts blurs the picture somewhat. The essential difference is twofold; firstly the age for great scientific achievement seems indisputably under 40 and, as discussed above, there’s plenty of evidence to support the under 30 theory as well. Secondly, unlike the arts, very few scientists seem to go on and on making creative discoveries. The absolute discipline of science clearly has its limits – the level of mental agility and concentration required simply to undertake the maths, let alone think creatively, might account for why scientists give up on making giant leaps after 40. Witness Newton who spent so much of his later life seeking the Philosopher’s Stone, sticking needles behind his eyes and staring directly at the eclipse or Paul Dirac who, after connecting classic and Quantum physics with his equation, grumbled on for years about its inelegance and kept up a regular correspondence with NASA about his certain contention that rockets would do better to take off on their sides. Scientists would appear to be living proof of the uncomfortable truth about our shrinking brains. Science itself has proved irrefutably that as we age so we lose neurons and our mental capacity declines – mentally we’re just not as swift and agile at 50 as we were at 30.

Paul Dirac. Spent a large part of his later years arguing his case with NASA

that rockets should take off horizontally.

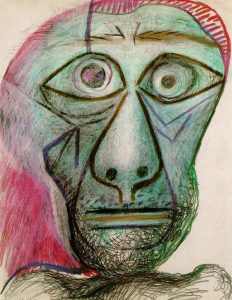

Are Painters the exception?

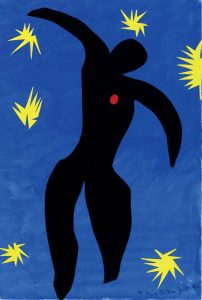

I had a hunch when beginning this article that painting might be the discipline that breaks the mould. So many of the greats seemed to be creating works of incredible originality almost to the moments of their death. Picasso’s beguiling 1971 self-portrait, Matisse’s late scissor work and Monet’s water Lilly series are all examples of the artist growing creatively in their so-called declining years. From a public perspective their ‘great’ works might have been behind them. Picasso, perhaps the greatest of them all, had painted the works for which he is most famous (and most energetically traded) over two decades before he died. But that’s perception, the truth is quite different. Do the so-called late works of great artists hold the key to unlock the best work under thirty conundrum?

Matisse’s The Fall of Icarus. Part of the deceptively simple cut outs (gouaches découpés).

WM Turner’s Rain Steam and Speed the Great Western Railway. The representational collapses into the abstract – 60 years before its time.

The list of late great achievers in the world of art is extensive; Titian’s Flaying of Marsyas, far too modern for the late sixteenth century and painted when he was 89, Goya’s black paintings forged from the loneliness of total deafness and any one of Turners ethereal late works that collapsed the representational into the abstract and anticipated art that would not appear for at least another 60 years, are just some amongst many.

Titian’s Flaying of Marsyas, far too modern for the late sixteenth century

But perhaps one painting and one artist stands above them all; Rembrandt’s so called Kenwood Portrait.

Painted in 1662, just seven years before his death. With it’s perfectly executed geometry combined with a sublimely and scuplterly self-portrait, it bestrides the years between youth and age. On the wall behind the artist are two perfectly executed semi-circles which have long defied interpretation for the perfectly good reason that there is nothing to interpret. Rembrandt, much sneered at throughout his life by the purists who adored Rubens for giving them what they wanted but reviled Rembrandt because he wouldn’t, cock’s a snook at his critics with this dextrous display of draughtsmanship. At a time when one might imagine his fine motor control may have begun to wane, he pulls of a mighty feat of muscular control. One can imagine the irascible old Dutchman saying, “There you go you barshtards, I can do that … now, let’s return to the art.” And what art. In one of the last of his 300 or so self-portraits we have a work of absolute genius that would have definitely been rejected by the 1860s Paris Salon. ‘Unfinished’ was the common complaint of the critics of the Impressionists and looking at the artists hands, blurs of brush-work, Rembrandt would definitely been consigned to the Salon des Refusé bin. The white of his hat foretells the acid white of Manet’s Olympia and the curls of his hair, somewhat white also, still retain a youthful springiness. But it’s the gaze of wisdom that is the most arresting. Here is a man at the height of his powers, supremely confident with over forty years of innovation and excellence behind him – the flame of creativity not dimming but roaring.

So the scientists are all washed up by forty and by fifty, the poets and novelist who perhaps recognise that they will never be as angry or motivated as they were when they wrote their best works. Haunted by this, and creeping cynicism for what they do, they slope off into ordinariness. But for the painter the creative demon can never be slain, only tamed.

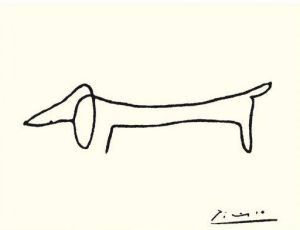

There is a story, probably apocryphal, that Picasso was once asked how long it had taken him to draw his famous sketch of his dachshund. “80 years” he replied. Whether this is true or not he certainly once said that he could draw “like Raphael” when he was young. “But it has taken me my whole life to learn to draw like a child”. This is a heartening thought as in losing innocence, we lose the total creative freedom we had at five years old when confronted by a blank sheet of paper and a box of paints. How reassuring to think that with a life-time of practice we might one day recover it.

Picasso’s Dachsund: 80 years in the making.

But there it is; ‘a life-time of practice’. It seems that we are all subject to Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours rule. Any chance then of me doing something ground-breakingly creative at 57? I think we can say a big, fat, ornately embroidered ‘No!’. But then, as my wife somewhat cruelly but nevertheless truthfully observed, did I ever think I would?

Ok then, where’s my lawnmower?

Notes

- It’s not technically true that Rutherford split the atom. This is a fine example of historical short-hand. In fact his team at the Cavendish laboratory did, albeit under his direction, but somehow ‘Rutherford split the atom’ rolls off the tongue better than ‘The students and postgraduates at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge split the atom’ so the prize goes to the wily old Kiwi.

- Ada Lovelace was the only legitimate child of Lord Byron who might also easily join the ranks of the ‘best work under 40’ brigade. Although He was actually 41 when his masterpiece Don Juan was published you get the point.

Martin Roberts

Latest posts by Martin Roberts (see all)

- Why using your hands might be good for you - October 13, 2017

- Have we done our best creative work by 30? - September 25, 2017

- The Madonna of Sant’Agostino - September 12, 2017