In a recent clear out of the Nicholson family attic the following letter between the artist Graham Sutherland, fellow artist and friend Edward Nicholson came to light. Its contents throw new light on an age-old artistic scandal.

Hotel Negresco

Nice

September 1966

My Dear Nicholson

Katharine and I have come to Cannes for a few days. The season is over and we shall not be much bothered by the kind of crowd who haunt the town from June to August. There are a few Americans left as, having much money and even more time, they now cannot seem to be parted from the continent that they all worked hard to leave. I suppose, as the prodigal children, they enjoy parading their wealth to us poor souls who were left behind, even if they secretly know it all to be such vulgar hauteur. The Negresco1 is full of them and it grieves me so to see the French, normally so dignified (if not a little haughty themselves), bowing and scraping to gather tips left by farmers from Iowa and Texan cattle barons. But such is the way of things.

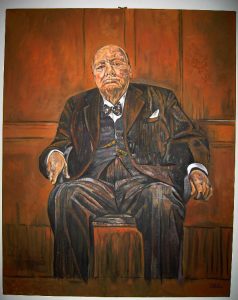

However, my dear Edward, it is not the trivialities of the fin de season that have driven me to the escritoire, besides I know you have no interest in such things. It is, of course, the news concerning Lady C2 and the destruction of my painting of Winston. Or perhaps I should say – final destruction, for heaven knows she must have considered it a thousand times since the unveiling and WSC’s3 unworthy response. But the deed is done and, on first hearing of it, my response was one of complete indifference. I have never, as you know, felt the sentimental attachment to my works suffered by other artists. This painting was lost long ago and its actual destruction was neither closure nor dramatic denouement.

But this morning I took a short walk down to the promenade, quite early when only the flower sellers in the market4 were about and the fishermen in the harbour were still landing their catches and I began to reconsider my feelings. Perhaps it was the hour, but I found myself in an unusually reflective mood and was rather surprised by the darkness my thoughts. By the time I had re-gained the hotel I was quite determined, in spite of Katherine’s insistence that I come to breakfast, that I should take up my pen and write to you – for you alone would truly understand what it is I have to say.

As you know I am not one given to melancholy, but as I walked my mood became more and more bleak. At first I was angry – this surprised me the most – but before long I found myself becoming increasingly desperate. But it was neither the picture, nor its destruction that grieved me, it was the light that the whole incident threw on the man himself and upon the history of the terrible years that he had guided us all through.

You will call me naïve, but I confess that I would have counted myself amongst those in Britain who regarded the man as intouchable. I grew up in age when we truly believed that we Britons were special and that King Arthur would always return in hour of need. Would you ever admit to being amongst those, who, like me, believed that Churchill was nothing more than living, proof of the legend? Of course not Edward, you are far too sensible for such nonsense, but I think you will understand when I say that Churchill exercised a powerful influence over us which extended some way beyond the drunken knave that we all really knew him to be.

Of course you know that I do not really believe in such foolishness either, at least no rational part of me does. But he lived in our imaginations and I was brought to my present state by the awful realisation that I, quite unintentionally, had been the one to show us how dull we had been.

As I worked on his portrait I was driven by an urge (who knows demonic) to show him not as he has been but as he was sitting before me. Trust me when I say that there was none of the inverted vanity that existed between Lely and Cromwell5 , none of us have ever fallen for that. It was just that I had a notion of Churchill as the venerable old man, tired, care-worn, somewhat humbled but still a rock. When it was unveiled I confess that I was amongst those who laughed as both Houses laughed6; Churchill the wit, the man with les mots just for the moment. I thought then that this was nothing more than a feint, something to please the crowd by the greatest crowd pleaser of all time.

But as I walked this morning it gradually came to me that Churchill was no Lear, neither foolish nor fond. Here was no tired tyrant but Ozymandias7 and I, my good friend, the sculptor. But it was not my hand that well the passions read; some invisible hand moved my brush to reveal curled lip and broken stones8. It was this that Clementine saw and this that she destroyed.

It cannot be denied that I gave it to him and that, in so doing, to her. Who can blame a wife as long-suffering as her to wish to preserve his reputation and, by extension her own. But the flames that consumed it (for surely fire it was) were none other than the flames that burned Coventry and Dressden9. The heat was just the same as Savonarola or the Nazi Students in ‘3310. At that moment, as I stood looking out at the calm Mediterranean on a warm late summer’s morning, Churchill was now more or less noble than Hitler or Mussolini, it was just he that had won. God forbid that a clumsy artist from Streatham should reveal it.

I know that I can trust you, dear Edward, to keep these thoughts to yourself, at least until I am in a place where I shall not hear the hoots of derision that would inevitably follow their revelation. I am only happy that I can rely on you to understand how I feel at this moment. You are a good friend who mitigates the pain felt by us foolish and fragile artists by your intelligence and wit.

Sutherland.

Notes

- The Negresco was the most fashionable hotel in Nice at the time the letter was written

- Lady C: Lady Clementine Churchill – wife of Sir Winston Churchill

- WSC: Winston Spencer Churchill

- Flowers: Sutherland is almost certainly referring here to the flower market in the Cours Seleya, which he certainly would have passed on his walk from the Negresco to the harbour. Although the Cours Seleya became a car park in 1930 there was still a weekly market if not the grand shops, cafés and restaurants for which it was famous in the nineteenth century and today since its restoration in 1980.

- Sir Peter Lely was the artist who painted the famous picture of Oliver Cromwell which portrayed the Lord Protector, at his own request ‘warts and all’.

- The painting of Winston Churchill by Graham Sutherland was commissioned by both Houses of Parliament to commemorate Churchill’s 80th birthday. When it was first unveiled, before the assembled members, Churchill quipped, to much amusement, that it was ‘certainly a fine example of modern art.’

- Lear / Ozymandias: Although Lear’s decision to abdicate in favour of his daughters turned out to have disastrous consequences, the original motive was simple enough; to divest himself of political power and to enjoy a well-earned retirement amongst his family. ‘Foolish and fond’ is Lear’s own description of himself (Act 4, Scene 7). Sutherland point is that Churchill clearly had no such intentions but rather was more akin to Shelley’s Ozymandias, the absolute tyrant.

- Well the passions read: In Ozymandias Shelley uses the sculptor to represent the common man against tyranny. The famous ‘wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command’ are the passions that the sculptor ‘read’ and this is, ironically, all that remains of Ozymandias’ power. Sutherland both aligns and distances himself from this by identifying himself with the sculptor whilst shifting the blame for his work of revelation to an invisible hand. It’s possible also that this references Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’, which he used to describe the inevitable and unavoidable forces of capitalism. Just as the invisible hand drives the market so a similar force drives the artist’s hand to expose human folly.

- The fire bombing of Dresden in February 1945 was largely justified by the incendiary raid on Coventry by the Luftwaffe five years previously.

- Savonarola / Nazi Students: The burning on thousands of objects of cosmetic art and books on 7th February 1497 by the Dominican priest Girolamo Savonarola was the original Bonfire of the Vanities. In May 1933 students from universities across German carried out their own bonfire of vanities by burning thousands of books regarded as un-German. Sutherland clearly saw the destruction of his own work in the same light; as a tyrant brooks no discussion of his absolute power and absolute greatness, the painting had to go.

Martin Roberts

Latest posts by Martin Roberts (see all)

- Why using your hands might be good for you - October 13, 2017

- Have we done our best creative work by 30? - September 25, 2017

- The Madonna of Sant’Agostino - September 12, 2017